Blade Runner: The Final Cut

© Warner Bros. Pictures

What makes us human? Adapted by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples from Phillip K. Dick’s novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER (originally released in 1982; now in its fourth incarnation) explores this question through the story of Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a police officer who “retires” synthetically engineered beings called Replicants. Four Nexus-6 Replicants have escaped from an off-world colony, where their kind are used as disposable labor in harsh conditions unsuitable to humans. Zhora (Joanna Cassidy), Leon (Brion James) and Pris (Darryl Hannah) are led by the calculating Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer). Either the studio did not afford Scott the time, or he didn’t care enough to show us, so everything I’ve just described is relayed in an expository opening crawl.

Saturated with images establishing the decrepit future of Los Angeles, 2019, Scott’s picture revels in postwar dystopian slang, a crumbling world wrought by specific oppression rather than benign negligence—the dilapidated Bradbury, impoverished Asian-American commoners muttering Esperanto or the like, and off in the distance, gleaming pyramids representing the monolithic Tyrell Corp, manufacturers of the Replicants—all suffocated in smoggy, diffuse light flashing through window shades as if we didn’t already know from the hammy Hammett dialogue that this a film noir.

Deckard uses a standardized psychological test, called the Voight-Kampff, to profile suspected Replicants and identify them on the basis of their lack of memories or normal emotional responses to provocation. Invited to meet the founder, Mr. Tyrell (Joe Turkel), Deckard’s asked to administer the test to Rachel (Sean Young), a next-generation Replicant with memories implanted in the hope of fostering better emotional stability and human interaction. Replicants have been given a four-year lifespan to prevent stunted emotions—a consequence of not having memories. Rachel has both memories and a limited lifespan, and she shows up in an alley precisely when Deckard needs her to, but never mind.

The only characterizations that work for me are Cassidy’s Zhora and Hauer’s Batty. Zhora, an assassin from a “kick murder squad” (whatever the hell that is), survives as a dancer in a seedy bar run by a stereotypically loathsome owner, Taffey Lewis (Hy Pike). Zhora’s intensity and desperation followed by her public execution gains our empathy; did Deckard really have to kill her if she was going to die anyway?

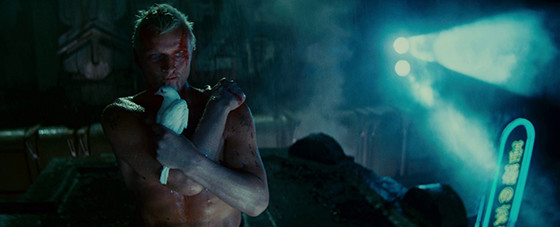

If I were to ask anyone what defines the characters of Rachel or Pris, they might answer, “shoulder pads and cartwheels”. All the detail is focused on how these women look—window dressing without the window. Only Rutger Hauer is afforded the opportunity to chew scenery, figuratively and literally as he bashes his head through a wall and takes a nail through his palm. Can Christ metaphors be any more sophomoric than that?

Scott’s story makes less sense than its individual images. He attempts to connect the world visually through Mayan and Egyptian architectural motifs, occasionally stumbling his way into beautiful static triumphs of set and costume design, yet never connects them into a whole as Deckard trundles about the city hunting down the four Replicants. A descendant of BLADE RUNNER, Alex Proyas’ sci-noir, DARK CITY, at least followed through with the question it begged about the core of humanity and the seemingly constructed nature of its contiguous world drowned in perpetual darkness. Deckard (which my computer, apropos, keeps auto-correcting to “dickered”) is too busy chasing Replicants.

BLADE RUNNER doesn’t engage you directly; it forces passivity on you. It sets you down in this lopsided maze of a city, with its post-human feeling, and keeps you persuaded that something bad is about to happen. Some of the scenes seem to have six subtexts but no text, and no context either. – Pauline Kael

Like Nolan’s INCEPTION and Kubrick’s 2001, Scott’s works are really shallow, action set pieces masquerading as profound science fiction. His films are themed, generally, in simplistic terms for broad consumption: David vs. Goliath, man vs. industry, good vs. evil, us vs. them. Only in subsequent re-edits did Scott reverse engineer the character study, but in the wrong direction. The Director’s Cut and Final Cut versions of the film show Deckard dreaming of unicorns. Later, his sidekick Gaff (Edward James Olmos) leaves an origami unicorn at Deckard’s doorstep, implying that the dream or memory is implanted. Various writers including Frank Darabont, have argued that the change, and Scott’s concrete confirmation in interviews, undermines the film’s morality. As a human, it’s transformational for Deckard to gain empathy for Roy who ultimately accepts his own fate in a stunning, existential soliloquy that Hauer crafted on set. As a Replicant, Deckard’s just looking out for his own kind. It upends the entire meaning of the story, not that there’s a coherent one to begin with.

BLADE RUNNER is excessively praised for its visuals as well as its score by Vangelis, shallow compared to the Maestro’s other compositions and riffing heavily off the mood pieces in his homage to film noir, The Friends of Mr. Cairo, released a year earlier. As much I am a fan of Vangelis’ work, I agree with Kael that, like his accompaniment of Scott’s dreadful 1492: CONQUEST OF PARADISE, the electro-orchestral score overwhelms the imagery and dialogue, or perhaps Scott isn’t skilled enough to keep up with Vangelis’ grandiosity. I don’t know if that’s a compliment or an insult.

BLADE RUNNER: THE FINAL CUT is playing in a limited run at the Texas Theater.