The Lake House

Kate Forster (Sandra Bullock) lives in a glass house (please, no jokes involving stones…) in the woods, near a quiet lake. As with all romantic stories (especially those involving Sandra Bullock), she’s a luckless type who drives the obligatory beater, despite somehow being able to afford an architecturally-iconic house in the…

Kate Forster (Sandra Bullock) lives in a glass house (please, no jokes involving stones…) in the woods, near a quiet lake. As with all romantic stories (especially those involving Sandra Bullock), she’s a luckless type who drives the obligatory beater, despite somehow being able to afford an architecturally-iconic house in the…

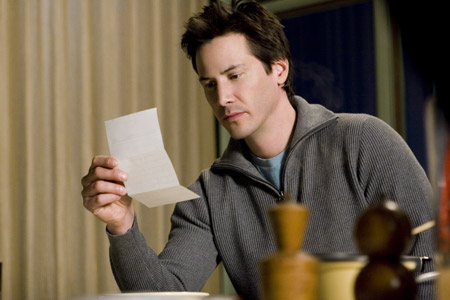

and Village Roadshow Pictures’ “The Lake House,†also starring Sandra Bullock.

Photo by Peter Sorel

I know it’s cliché to say it, but if ever there were a film that begs the question, it’s this one. So, I ask you: What the hell were they thinking? This is intended to be a movie about lives that are out of synch, but the film itself is suffering from arrhythmia.

Kate Forster (Sandra Bullock) lives in a glass house (please, no jokes involving stones…) in the woods, near a quiet lake. As with all romantic stories (especially those involving Sandra Bullock), she’s a luckless type who drives the obligatory beater, despite somehow being able to afford an architecturally-iconic house in the Chicago area. In a cheap and obvious transition of time, it’s suddenly snowing and another beater (what a coincidence!) pulls up to the house. Surprise, it’s Keanu Reeves—an equally mediocre actor—as building developer Alex Wyler, son of famous architect Simon Wyler (Christopher Plummer). The point is made in a fashion too obvious to ignore, and yet intentionally yet unnecessarily vague, as if the trailers hadn’t already made it clear that Wyler and Forster are seen in different time periods.

Though Wyler has a girlfriend, he becomes introduced to Forster by way of a letter that welcomes him to what used to be her home. Meanwhile, somewhere in Wisconsin in 2006, the lonely Forster is practicing medicine at a local hospital. Saving lives is her gig… every one but her own, get it? Remind you of any other women leads in romantic shlock? Faster than you can say “plot device,” a man gets hit by a bus… hit by a… bus! That was the punchline to “Scary Movie 4,” only it was funnier because it involved James Earl Jones.

Wyler also has the proverbial broken relationship with his father, Simon. All fathers in these idiotic movies are curmudgeons who either don’t understand, are misunderstood, or both. And they have the most monochromatic of dynamics… The extent of their damaged relationship is boiled down to a singular difference: The father is an architect while the son is a developer. One builds lots of cheap, cookie-cutter housing to make loads of money. The other builds elaborate and narcissistic custom designs that probably fetch millions each. To-may-to, to-mah-to. Is there anything else to their mutral hatred? Nope.

The acting will most certainly set you off. Conversations between Forster and her coworker, Anna (Shohreh Aghdashloo) or with her mother (Willeke van Ammelrooy) are stilted, leaving gaping holes of silence where one wouldn’t expect them to fall in such discussions of the mundane as are had here. And that’s also the extent of these peripheral roles—monochromatic support systems for the star actors, devoid of any deeper character or purpose.

It’s odd, but now I can say I’ve seen a movie which makes the timing of character interaction in the “Star Wars” prequels look fantastic. Whereas in those movies the actors were often working their timing against computer-generated characters that were added in post-production, here the actors in real settings seem to behave as though their parts are being performed at separate times and then edited together as though by potato peeler and scotch tape. The cinematography is likewise erratic. At times it’s conventional, and then in other instances it goes for the artsy angle: A reflection shot of Wyler looking out his window zooms in abruptly and jarringly like a war documentary push-in. Neither the lilting (read: trite) score nor the context of the scene match the method used, so we’re not sure what the hell the director’s trying to say. The worst kind of message is one that’s forcibly crammed down the throat, leaving the taste buds no time to sample it, and the teeth no time to chew on it.

The two starcrossed morons send letters to one another through their magic mailbox—one instant he drops it in the mailbox, and then it appears in her time. Now, let’s ignore for a second that the film doesn’t do anything about this phenomenon… The two embrace it as if nothing particularly unimaginable is going on. Nobody calls the Guinness Book or Stephen Hawking to report an unprecedented discovery. In typical fashion, the pair keep the remarkable incident to themselves which helps facilitate a misunderstanding that could easily have been avoided with witnesses to help corroborate what’s going on.

Even setting these criticisms aside, it strikes me as perversely stupid that neither of them sends a picture through the mailbox. That might have circumvented the two biggest paradoxes in the film. One involves an event that can be avoided, and if you didn’t already figure out what it is by the first twenty minutes, you shouldn’t be driving a car, using the internet or reading this commentary. Clearly it’s a different season in Forster’s present than in Wyler’s. Certainly we see an inexplicable and immediate change of season that suggests that time and nature aren’t fixed and immutable. And even yet it’s demonstrated that changes in the past have immediate consequences in the future, yet there are changes to the past that of which Forster is consciously aware (even though she shouldn’t be, as her entire past has also changed). All this begs one glaring question: Why does every letter sent through the mailbox, forward AND backward in time, appear in a linear order equal in passage of time? In other words, when that really, really important letter has to be sent to Wyler, what in the universe (save an insistent director with a fabricated catharsis that must arrive on cue) prohibits it from arriving with plenty of lead time?

The Lake House • Dolby® Digital surround sound in select theatres • Running Time: 105 minutes • MPAA Rating: PG for some language and a disturbing image. • Distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures

The Lake House • Dolby® Digital surround sound in select theatres • Running Time: 105 minutes • MPAA Rating: PG for some language and a disturbing image. • Distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures