Transamerica

Bree Osborne (Felicity Huffman) is the kind of woman who, well, isn’t entirely a woman… yet. “This is the voice I want to use,” she says, repeating words from an instructional cassette, but in a quivering male voice — attempting to sound more feminine. She works as a telemarketer for Home Shopping Club, and regularly seeks the counsel and encouragement of her therapist and friend…

Bree Osborne (Felicity Huffman) is the kind of woman who, well, isn’t entirely a woman… yet. “This is the voice I want to use,” she says, repeating words from an instructional cassette, but in a quivering male voice — attempting to sound more feminine. She works as a telemarketer for Home Shopping Club, and regularly seeks the counsel and encouragement of her therapist and friend…

Bree Osborne (Felicity Huffman) is the kind of woman who, well, isn’t entirely a woman… yet. “This is the voice I want to use,” she says, repeating words from an instructional cassette, but in a quivering male voice — attempting to sound more feminine. She works as a telemarketer for Home Shopping Club, and regularly seeks the counsel and encouragement of her therapist and friend, Margaret (Elizabeth Peña).

As her physician, Dr. Spikowsky (Danny Burstein), informs her (and the audience), Bree is gender dysphoric. Gender dysphoria, or Gender Identity Disorder, occurs when a person is assigned one gender on the basis of their physiological sex, but identifies with the other. The DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), published by the American Psychiatric Association, identifies five key criteria that must be met for a person to be diagnosed with GID. Like clinical depression, GID is a real condition with real detriments suffered by those who have it.

Bree is about to undergo the process of sex reassignment, and is extremely nervous about it. But more crippling than that has been her lifelong inability to cope with being a woman trapped in a man’s body. She’s had to use all kinds of prosthetics, make-up, hair removal, and hormone therapy but still lacks the internal plumbing that, she feels strongly, will complete her sexual identity.

Her personal crisis is interrupted when she’s called to bail out her son, Toby Wilkins (Kevin Zegers). Margaret recommends Bree confront her history head-on, before she can be free to deal with her new identity.

Toby had a stepfather who, suffice it to say, was extremely abusive. His mother killed herself — shut in the garage with the car on. Toby found her one day as he came home from school. The jail’s willing to let him go for a dollar, mainly because they don’t know what else to do with him.

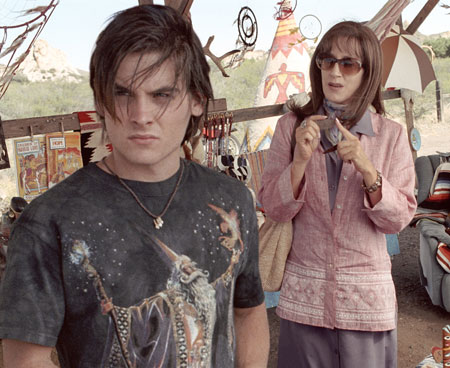

At first, Toby has no clue that his mo- er, fath- parent is transgendered. They travel through several towns and the countryside, encountering various people along the way. Old men stare. A little girl asks, “Are you a boy or a girl?” Toby continues to test her patience, and loses it when he realizes she is a man. “You know, social ostracism doesn’t work in a community of two,” quips Bree.

While Toby is, in his own way, passionate and excitable, Bree spends most of the duration of this movie as if she’d just attended a funeral. Morose is a word I like, but it’s not painfully long enough to describe the agonizing pace of the first two-thirds of this film. Things begin to pick up only when they meet Calvin (Graham Greene), who’s Zuni/Navajo, and a hitch-hiker who’s a self-professed “peyote shaman” — his way of saying he likes to get high every now and then.

Calvin’s casual perspective on the world lends him to easily accept Bree for who she is. There’s an exchange between Toby and Calvin regarding Bree that I won’t reveal, except to say that it reminds me of Joe Brown’s riotously funny closing line in Billy Wilder’s “Some Like It Hot.”

When they reach Bree’s parents residence, her mother, Elizabeth (Fionnula Flanagan) is aghast at the sight of her transformed son, yet oddly transfixed on the discovery that she (Elizabeth) has a grandson. Bree’s treated like a second class citizen, whereas Toby is worshiped. But Bree has a close kinship with her sister, Sydney (Carrie Preston) who, as the young troublemaker in the family, does manage to deflect some of the parental disappointment away from Bree — if only temporarily.

The mother is a caricature, though, like many parents in movies who exhibit utter bewilderment at their child’s chosen profession, identity or what have you. And this is one of the major problems with this film, in addition to the aforementioned pacing: Monochromatic emotional obstacles are set up like pins to knock down via some great family catharsis. Interpersonal and family dynamics, especially, are far more complicated in real life. Once I would like to see a movie about a family that doesn’t awaken through a phony, abrupt revelation, but rather straddles their individual natures while grappling realistically with their own incomprehension.

The father-daughter relationship in “Say Anything” is an excellent example of a believable portrayal — of a daughter struggling with her own identity issues while the father, not entirely good and not entirely bad, tries to understand what it is to be an adolescent, stuck like an outsider between the clearly defined roles of childhood and adulthood. I know some will argue with me that being a parent of a “normal” teenager with “normal” teenage problems is vastly different than being the parent of a transgendered person. I would contend that it’s only different from the eyes of someone outside that family.

It’s not that there aren’t obstinate parents who, after nearly two-decades of rearing their child, simply refuse to appreciate them for who they are… but because Bree’s parents weren’t simply flat-out deadbeats, I find it hard to believe that anyone who invests that many years in a child hasn’t the capacity to understand them, even if they don’t accept them. There’s simply no complexity to this family dynamic beyond a rudimentary scaffold.

Transamerica • Dolby® Digital surround sound in select theatres • MPAA Rating: R for sexual content, nudity, language and drug use. • Running Time: 103 minutes • Distributed by The Weinstein Company

Transamerica • Dolby® Digital surround sound in select theatres • MPAA Rating: R for sexual content, nudity, language and drug use. • Running Time: 103 minutes • Distributed by The Weinstein Company

Â