The World’s Fastest Indian

The names John Cobb, Malcolm Campbell, Mickey Thomas, Craig Breedlove and Richard Noble mean so much to so few people. Perhaps even fewer know of Burt Munro, who in 1967 set a class speed record for motorcycles under 1000cc at the Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah. Munro’s accomplishments are notable, but at the height of the space program were quite possibly overshadowed by the test pilots of Edwards Air Force Base, and…

The names John Cobb, Malcolm Campbell, Mickey Thomas, Craig Breedlove and Richard Noble mean so much to so few people. Perhaps even fewer know of Burt Munro, who in 1967 set a class speed record for motorcycles under 1000cc at the Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah. Munro’s accomplishments are notable, but at the height of the space program were quite possibly overshadowed by the test pilots of Edwards Air Force Base, and…

The names John Cobb, Malcolm Campbell, Mickey Thomas, Craig Breedlove and Richard Noble mean so much to so few people. Perhaps even fewer know of Burt Munro, who in 1967 set a class speed record for motorcycles under 1000cc at the Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah. Munro’s accomplishments are notable, but at the height of the space program were quite possibly overshadowed by the test pilots of Edwards Air Force Base, and the astronauts of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs. However, what Chuck Yeager is to Phil Kaufman’s “The Right Stuff,” the plucky 60-something Munro parallels in “The World’s Fastest Indian.”

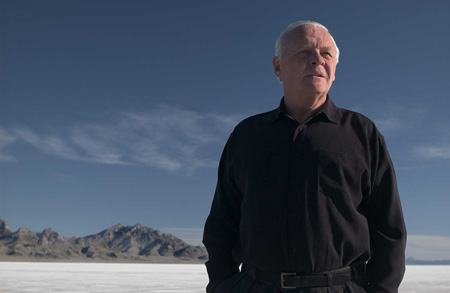

The film opens with a tracking shot of a beaten-up equipment shed, sweeping past a strange looking motorcyle contraption and a shelf of various, apparently destroyed motorcycle parts with a wooden sign reading, “Offerings to the god of speed.” The sign is a reference to director Roger Donaldson’s 1971 documentary—of the same name—about Munro. Munro (Anthony Hopkins) is sleeping, dreaming—racing down a straightway only to come face to face with himself. The film cuts immediately to Munro’s face, showing age and maybe a bit of desperation—as if there’s some task nagging at him in the middle of the night.

It would appear that his mornings routinely consist of pissing off the neighbor, George (Iain Rea), with engine noise and an unkempt lawn. Tommy (Aaron Murphy), George and his wife’s young boy, often visits the eccentric Munro. Munro has as powerful a desire as any to come to the end stage of his life having felt the time was well-spent. So, he clinks away at his 1920 Indian Scout motorcyle—even building his own piston heads out of recycled Chevy and Ford steel.

He shaves the rubber off the tires with a knife, explaining to Tommy the effect of centrifugal force on the tire’s geometry. Tommy is, of course, the young boy who helps the kooky senior next door. It is, however trite, a role that seems necessary in a film like this. Every crazy old innovator has to have a young, optimistic kid from a generation or two ahead helping him out—whom he can mentor and inspire. So, Tommy dutifully assists Burt with the acquisition of some needed tools, e.g. a knife from his mom’s kitchen. However, Donaldson (who previously directed Hopkins in “The Bounty”) is wise enough to center the story not on a tedious subplot but on Munro’s experiences on his journey to Bonneville. Will he make it there? Obviously. The interesting question is, “How?”

Munro is a genuinely likeable character. There are virtually no inflated conflicts in this movie, save perhaps the cliché of the jaded L.A. cabbie—a minor trespass. When you think that the Antarctic Angels—a biker gang that confronts Munro at a party held by the locals in his honor—are going to do something truly bad, they just want to challenge Munro’s claims about his motorcycle. Munro doesn’t win, but later, the bikers show good sportsmanship by wishing him well on his trip to America (and chipping in some beer money). In a lesser movie, the bikers would return some time later in the film in the midst of Burt’s comeback stride for a final, artificially-tense showdown.

To Burt Munro, Bonneville is “One of the few places on earth you can find out how fast your machine can go.” He’s not just talking motorcycles. If I were any other kind of critic, this is where I might be compelled to insert the words “triumph of the human spirit” or similar platitudes into this review. What drives a person like Munro? It’s not enough to make pedestrian declarative statements assuming his motivation. I’d rather ask the question and leave it largely to you, the audience, to see how the film tries to answer that question.

There are two primary forces in Munro’s life, as depicted in his travels across the ocean and the United States, to reach his destination in Utah. One is human nature. Most of us have the innate desire to do something, on some dimension, better than we’ve done it before… to tackle some goal that seems unattainable. Mine is the desire that some day I might write one tenth as well as Pauline Kael. The other force in Munro’s life consists of the many people, largely on whose kindness he makes his way. With his genuine charm and enthusiasm, and knack for sharing interesting, if seemingly far-fetched, anecdotes, his personality alone persuades others to like him such that they offer to help him. In the age of endless publication of reams of inwardly-focused self-help diatribes, scenes of conversations that exist here merely to establish character without the contrivances of plot read like the infinite interpersonal wisdom of Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People.

From the US Customs agents at his port of entry, to the transvestite working at the motel on Sunset Boulevard, to the used car salesman played by comedian Paul Rodriguez (perhaps a nod to Robin Williams in Donaldson’s “Cadillac Man”), a Native American who happens to have a rather unsavoury but functional remedy for Munro’s prostate, and a multitude of inspired observers at Bonneville who want nothing less than to help this man who traveled half-way around the world to follow through on his dream, Munro leaves an indelible impression upon each and every one. Is it hokey? Kind of. But it’s played by Hopkins and the supporting cast with such personal enjoyment, and directed in such a straightforward manner without gimmickry or unnecessary dramatic devices—the only exception being a genuinely clever “rocket cam” point of view that closely rivals the visual sensation of any similar cinematography in the considerably larger 65mm IMAX format. The question isn’t whether or not he’ll transcend the bike’s, and his, limits. The question is, “How much farther over the edge will he push it?”

I remember as a child reading the Guinness Book of World Records, and being absolutely astounded by Richard Noble’s world record at Bonneville in Thrust 2—essentially a turbojet with wheels. I’m even more dumbfounded by the knowledge that in 1997, Noble and his engineers broke the sound barrier on land with a speed of 763mph. But there’s something incandescent about a sixty-something in a then 40-year old motorbike breaking 200mph in the 1960’s. As perhaps a lesson to those of us who foolishly set our bar relative to our neighbors or coworkers, Munro seems to have set for himself the ultimate goal of striving to be better than himself.

The World’s Fastest Indian • Dolby® Digital surround sound in select theatres • Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1 • Running Time: 127 minutes • MPAA Rating: PG-13 for brief language, drug use and a sexual reference. • Distributed by Magnolia Pictures

The World’s Fastest Indian • Dolby® Digital surround sound in select theatres • Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1 • Running Time: 127 minutes • MPAA Rating: PG-13 for brief language, drug use and a sexual reference. • Distributed by Magnolia Pictures

Â

Â