The Matrix: Resurrections

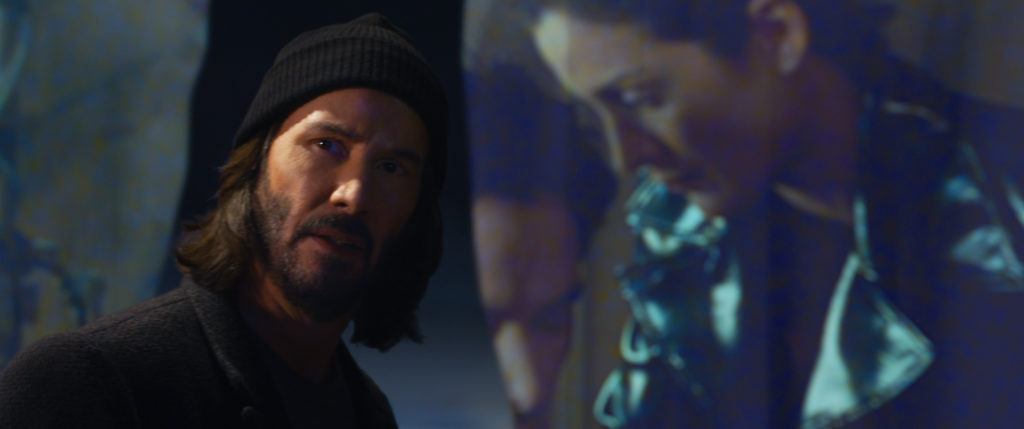

(L-R) KEANU REEVES as Neo/ Thomas Anderson and CARRIE-ANNE MOSS as Trinity in Warner Bros. Pictures, Village Roadshow Pictures and Venus Castina Productions’ “THE MATRIX RESURRECTIONS,” a Warner Bros. Pictures release. Image courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures.

The actors are in the matrix, that is, in the digitized system of things; or, they are radically outside it, such as in Zion, the city of resistors. But what would be interesting is to show what happens when these two worlds collide. – Jean Baudrillard¹

Doors, windows and mirrors play a recurring role in the Matrix franchise. You go through a door, you enter a bigger room, or world, as it were. If all the doors are closed to you, you go through a window. If you’re so full of yourself, you go through a mirror… at least that’s what Lewis Carroll taught us.

Eighteen years after the debut of the THE MATRIX, Lana Wachowski returns to the helm of the franchise, bringing back to life Neo (Keanu Reeves) and Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) who died in the original trilogy that spanned 1999 to 2003, intersecting with the dotcom collapse. For the uninitiated, the first three movies concerned the journey of Thomas Anderson (Reeves), a computer programmer, nagged by the feeling that he’s in a simulacrum of society that’s holding him and everyone else back from real enlightenment. Two sequels and an anime anthology followed, expanding upon the ongoing war between humans and machines.

Setting aside the overindulgence of the action-heavy sequels, THE MATRIX proffered pseudointellectual musings and fortune-cookie aphorisms. Initially so devoid of the point, the movie’s stilted tone made me laugh audibly; Baudrillard himself scorned the filmmakers for mangling his work, Simulacra and Simulation.

In MATRIX: RESURRECTIONS we gain the sense that the problem wasn’t a lack of imagination, but rather too much imagination for the studio overlords at Warner Bros. When it’s called out in-picture, we get the sense that it’s not a fabrication or exaggeration. But these endless meta-nods aren’t what makes RESURRECTIONS a compelling watch.

The movie begins by taking us back to the opening of THE MATRIX, but with different actors. We quickly learn that we’re inside a “modal” simulation—a program created to train an artificial intelligence, to do what we don’t yet know. Bugs (Jessica Henwick) and Seq (Toby Onwumere) drop in like digital spectators to study what this particular subroutine is all about. Bugs finds a re-creation of Agent Smith (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), who in turn finds himself at odds with his programming. They’re propelled into action by experiences neither can explain, yet they share one purpose—finding Neo.

From here we discover that Thomas Anderson is the developer of a hugely successful online gaming experience, The Matrix. Working on its sequel, Binary, Thomas struggles with what he believes to be mental health issues, dreams and delusions plaguing him—hallucinating images familiar to us as scenes from Matrices prior. A montage of his waking nightmares plays along to the tune of Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit”, inspired by Alice Through the Looking Glass, which Priyanka Chopra’s character—an easy guess for viewers of the sequels—reads in the corner espresso stop. That his business partner (Jonathan Groff) should take an interest in his sessions with his psychoanalyst (Neil Patrick Harris), is rather curious. His assistant, Jude (Andrew Caldwell), evokes the memory of Glenn Shadix’s more masterful performances as a similar kind of comically-grating sycophant in the late 80s and early 90s.

In the coffee shop, he meets Tiffany (Moss), an entrepreneur who builds and sells motorcycles—one of Reeves’ side ventures in real life. Where most movies would squander the moment on nonstop callbacks, the best of the entire affair takes place in a second conversation in which Thomas and Tiffany open up to each other about themselves and their mutual lack of fulfillment from their career successes. This becomes a springboard for the discussion about identity that, I think, Lana Wachowski wanted to have in 1999 but couldn’t articulate—either due to youth and inexperience, lack of clout, or the studio’s overwhelming disinterest in anything that didn’t push the action angle further. Thomas quips that the original Matrix “entertained a few kids.”

The new underground civilization, “Io” (dropping the “Z” and “N” for a play on the acronym for “input/output”), is led by Niobe (Jada Pinkett Smith), a former Captain of one of Zion’s many “ships” that travel on some kind of electromagnetic repulsion. Io serves as a refuge for humans as well as artificially intelligent “synthients” who fled the purge of programs from the original Matrix. Here the filmmakers revisit the musings of Anthony Zerbe’s character, Councillor Hamann, in RELOADED, on the interdependencies of man and machine.

I find RESURRECTIONS in my late forties so much more relatable than the passing, weird, at times ludicrously self-serious, action-oriented original. There’s a brainstorming montage for a proposed fourth Matrix movie based on the gaming series created by Anderson, that underscores the absurdities of commercial pressures and idiotic business proposals that the Wachowski sisters must have faced time and again.

But there the movie stops navel gazing and moves on to unresolved matters in its chunky, 148-minute running time which I’d bemoan, but part of the fun lies in watching the actors catch themselves in deep exposition with some self-deprecation and humor gravely lacking in the originals. We giggle when Morpheus (Abdul-Mateen II) parodies Lawrence Fishburne’s over-the-top delivery and bursts into laughter at doing so. This meta-Morpheus might induce groans if the nods propped up the series’ tropes instead of deconstructing them for a more mature audience perhaps tired of the loops and patterns of our own, daily existence.

In THE MATRIX, we learn next to nothing about Trinity. But if we take the franchise’s pilfering of Hindu and Buddhist philosophy at face value, The Trinity is simply another manifestation of The One. And so why don’t we know more about her story?

Playing with the notions of self, Tiffany tells Neo at one point not to call her “Trinity”. I wonder how many times Moss explained this to people who can’t separate the role and the actor. I’m reminded of a melancholy moment in LAST ACTION HERO in which Arnold Schwarzenegger’s movie persona confronts the real actor and tells him he’s brought nothing but pain and anguish.

Despite the fact that much of the fourth installment’s story about Trinity remains motivated through the lens of Neo, the film feels earned in terms of its self-reflection upon the Matrix franchise’s place in history alongside the evolution of the internet, the dangers it poses unchecked, but also because of the breathing room it gives the two principals to get to know one another for real. I left the first movie feeling no chemistry whatsoever, confused by the lack of character development. Why, save for some obscure rambling from the Oracle (Gloria Foster), should these two find each other interesting at all? Now at least we’ve a reason.

To give due credit, Moss and Reeves seem engaged in a dialogue about their real careers—both grappled with being typecast by the success of THE MATRIX. Reeves, a private person shaped by personal tragedies, plays his disillusionment with success superbly. We’re reacquainted with the archetype of the reluctant hero, the Arjuna, who attains enlightenment through skepticism turned inward on himself.

He indulges Bugs and others with the excitement of Kit Ramsey (Eddie Murphy) in BOWFINGER, who’s conned into a starring in a movie he doesn’t know he’s in. Thomas isn’t afraid of losing himself in this bizarre series of events if, by chance, it happens to relieve him of his anxieties about reality. He already conquered the illusion of self when he consciously rejected the idea of The One, the fair-skinned messiah of humanity.

Moss draws our attention to mechanisms of control seldom explored in male-driven films: gaslighting and domesticity—a deliberate narrative choice that the villain is a misogynist. Where other franchises use “it’s for kids” as a crutch, RESURRECTIONS meets audiences of the original where we are now—less cocky, more introspective —delving further into the inner lives of characters who have grown just as we have. It’s not the story I anticipated, but it works.

Conquering these distinctions of this self and that self, the filmmakers heed Baudrillard’s lesson and strive to fully embrace the message: That it’s not turtles all the way down. Rather, it’s turtles within turtles within turtles. Like the life of its creator, the story may have begun with a white male who finds that the answer is, in fact, his other half on the other side of the mirror, comfortable in her own skin.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

– Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

1. “The Matrix Decoded” interview in Le Nouvel Observateur, Vol 1, No. 2, July 2004.