Portrait Of A Lady On Fire

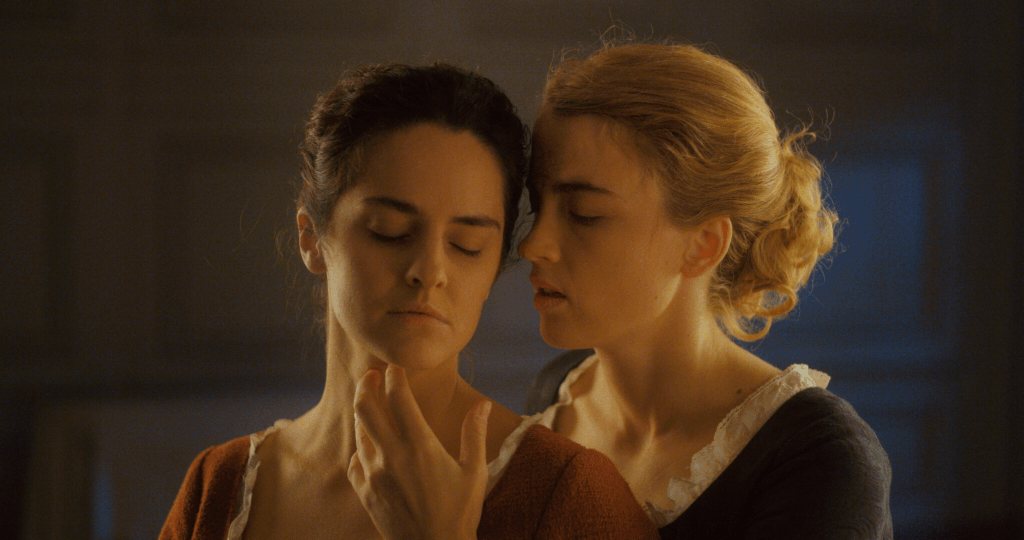

Noémie Merlant and Adèle Haenel in Céline Sciamma's PORTRAIT OF A LADY ON FIRE. Image courtesy NEON.

Queer love stories are among the most effective in recent pop culture. From CAROL to MOONLIGHT to Black Mirror’s SAN JUNIPERO, there exist myriad examples of romances outside the traditional, 18th century, heteronormative concept of love. Age of Enlightenment philosophers argued that pursuit of personal happiness, not economics, should inform ones choice of a spouse—a revolution that still often excludes the LGBT community.

Compelling straight romances buck societal norms: a couple from differing economic classes (or other cultural barrier) share a brief but intense romance, resolving in the death of one or the permanent separation of both. Often, this affair catalyzes the woman’s path of self-actualization through inspiration gleaned from her male lover. The most effective narratives convey that true love requires freedom, not possession. Céline Sciamma’s PORTRAIT OF A LADY ON FIRE is a simple, perfect distillation of this concept: if you love them, set them free.

Engaged to her late sister’s fiancé, Héloïse’s (Adèle Haenel) family commissions Marianne (Noémie Merlant) to paint a wedding portrait—a common practice to ingratiate courting suitors sizing up potential spouses. A companionship begins with silent walks, faces obscured by gauzy scarves. Marianne must observe her unsuspecting subject obliquely. Angered by her powerlessness to circumstance, Héloïse refuses to pose for the portrait serves as an act of defiance against her betrothal.

While memorizing Héloïse’s features piecemeal, Marianne becomes infatuated. Marianne’s attempted recital of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons Concerto 2 in G Minor (from memory), enraptures Héloïse. Slowly, the barriers between them draw back like their gauzy veils; in the short span of time it takes the commission to be completed, the two women fall into a passionate love affair that inevitably, they know, must end.

Employing sprawling tableaus of fire and water, Sciamma asks us to contemplate what defines freedom, captured in fleeting moments—some as simple as smoking a pipe, alone and naked, before a roaring fire. The contravention of Eighteenth Century romance—the idea that love by choice is superior to financial dependency—seems obvious, yet modern constructs of marriage still prioritize patriarchy over equality. That neither Marianne nor Héloïse can escape the social paradigm that confines them isn’t antiquated. It’s as relevant as ever.

The queerness of their relationship suggests an egalitarian dynamic, but the differences in their respective circumstances create imbalance. Trained as an artist—one of few professional avenues open to her—Marianne will one day inherit her father’s portraiture business. Héloïse aspired to a semblance of equality within the Benedictines—a convent that gave her the freedom to read and enjoy music—only to be ripped away with the death of her sister: “You can choose, that’s why you don’t understand me,” Héloïse tells Marianne.

A schism forms. Marianne has known a level of autonomy that Héloïse never has. She’s had sex and an abortion. She’s earned a living without needing a husband. Héloïse listened to pious organ music while Marianne attended the orchestra in Milan. Allowed liberties usually only reserved for men, Marianne is essentially Orpheus to Héloïse’s Eurydice.

The impending marriage symbolizes Héloïse’s death—a spiritual death, a death of choice. Unlike Orpheus, Marianne has no power to save her. She could offer a life of exile and secrecy, but she’d never ask Héloïse to reject her social obligation. When Orpheus glanced back at Euridice, he denied her freedom: to look is to possess. Like a portrait, Eurydice exists as a perfect, eternal snapshot in his memory forever.

A Disney tentpole released in the past year featured a heterosexual romance in which the woman achieved independence and self-actualization after the presumed death of her beau. But rather than let her flourish in his absence, he defies the rules of time itself to re-insert himself into a fulfilling life she’s already lived, resetting it so he can reap his ‘reward’. This stripping of her agency is anathema to love, yet the film packages this selfish, disturbing possession as a happy resolution.

“Turn around.” These simple words are Héloïse’s last to Marianne, granting her permission to look one, final time. Her agency intact, the story preserves in that crucial detail the true, selfless definition of love.