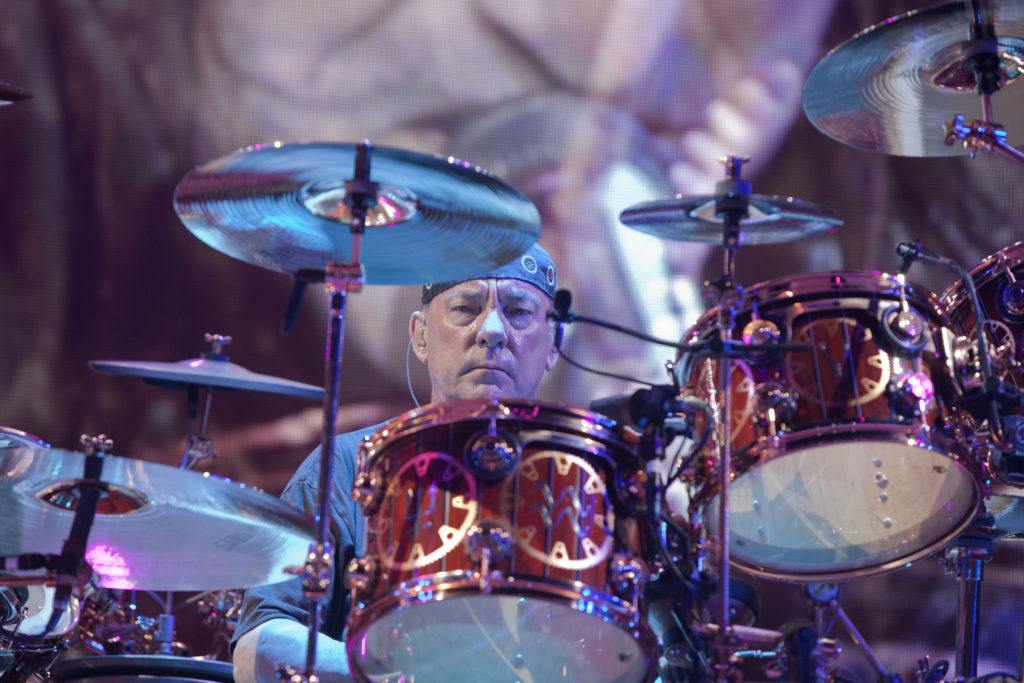

Time Stands Still: Neil Peart (1952-2020)

UNIVERSAL CITY, CA - JUNE 22: Neil Peart of the rock band Rush hits the stage for part of their Time Machine Tour at the Gibson Amphitheater in Universal City, CA on June 22, 2011. Photo: Harmony Gerber.

In 1994, during the Counterparts tour, at the peak of their popularity, their technical prowess, and the prime of their physical stamina, I watched Rush enthrall 17,000 fans at Minneapolis’ Target Center—a diverse audience spanning decades and ethnicities. In the declining years of progressive rock’s popularity, Rush fans seemed nonexistent, lurking in the weirdest of places, abruptly materializing en masse to descend upon Northeastern and Midwestern arenas as if the Solar Federation had sent its signal out from Toronto to every working-class city in the guitar-neck of America.

Like William Miller in ALMOST FAMOUS, I’d borrowed all my older siblings’ records and thus formed the core of my musical tastes. Raised in the Midwest, awash in AOR, CHR, Top 40, my cousin and sister rounded out the late 70’s breaking me in on an eclectic mix—Heart, Steve Miller Band, Zeppelin, The Beatles, KISS, the Eagles, Steely Dan, Brian Eno, Electric Light Orchestra, Van Halen, Triumph, Queensrÿche. In the 80’s, during the pre-Viacom MTV era, I discovered Talking Heads, Gary Numan, Eurythmics, Duran Duran, INXS, Missing Persons, Debbie Harry, Chrissie Hynde, Madonna. Russell Mulcahy’s music video for “Owner of a Lonely Heart” by Yes that tuned my senses to progressive rock.

A hypnotic pattern emerged, from Alan White’s backbeat, to Stuart Copeland’s, to Simon Phillips, to Jeff Porcaro, to Neil Peart. It wasn’t Rush’s wild success with the blue-collar anthem, “Working Man,” from their self-titled Moon Records debut on WMMS in Cleveland, Ohio, that caught my eye. That same year, John Rutsey’s health kept him from the band’s rigorous tour schedule, opening for Uriah Heep, KISS, Nazareth, Manfred Mann, and others. Rather fortuitously, Hamilton, Ontario, native Neil Peart replaced Rutsey and the band shifted from Cream-influenced blues rock to a progressive style most likened to the complex instrumentations and arrangements of King Crimson.

Neil Peart was by no means as sophisticated a drummer as any number of educated jazz percussionists, and many rock critics argued he’d a tendency to overcomplicate arrangements and lyrics to the point of absurdity. But his stilted, staccato 4/4 signature beat—with kicks on 1, 4, and 6, instead of 5—tricking many a listener into thinking they’re hearing some marvelously clever 7/8 riff, was the kind of thing that resonated with a kid trying his damnedest to search for something grander, even if he can’t yet handle it with finesse.

A short, skinny, brown immigrant with cerebral palsy, I nearly committed suicide enduring relentless bullying. But in my brother’s collection of CD’s and LP’s I’d stumbled upon “Subdivisions”, from Rush’s 1982 album, Signals. The simplicity and the metronomically-precise repetition, the lyrics describing the desire to escape small-town monotony, spoke volumes to an old-world boy trapped in a featureless, homogeneous, Midwestern cultural vacuum. Other tunes, like 1980’s “The Camera Eye” an ode to the electricity of metropolitan bustle, beckoned me from my rural cocoon to bigger and bigger cities.

From 2112 to The Fear Trilogy, Peart’s lyrics grew out of ideas from his favorite literature, namely at the time the polemics of Ayn Rand. He denied the connection, instead describing himself as a “Bleeding Heart Libertarian”. So it went, after waxing metaphorical on Trees, Bastilles, and Kings, Neil shifted his attention to tackling global subjects: social justice (“War Paint”), geopolitics (“Territories”), economic and gender inequality (“Heresy”, “Alien Shore”), late-stage capitalism (“The Big Money”).

Then, in 1997, his daughter was killed in a car accident, followed by his wife (cancer). While his many motorcycle journeys across North America distracted him, gave him purpose, it was clear that his mind and heart couldn’t return to the place they needed to be to keep Rush going. Among the most prolific acts in rock history—19 studio albums, 11 live albums, and 11 compilations—the rigors of recording and touring for forty years, time took its toll on the timekeeper.

Perpetual motion is natural to a drummer. One misstep can set you off your path, but you can either let the piece fall apart there and then, or you can course-correct and just keep going. It’s only natural that being a drummer is to be in a constant state of wanderlust…

Some will sell their dreams for small desires

Or lose the race to rats

Get caught in ticking traps

And start to dream of somewhere

To relax their restless flight

Somewhere out of a memory

Of lighted streets on quiet nights